May 21, 2018

Versions in 中文, Español, Français, 日本語, Português

[caption id="attachment_23528" align="alignnone" width="1024"] Brandenburg, Germany: in three advanced economies—Germany, the United Kingdom, and France—emissions have fallen despite the increase in incomes (photo: Caro / Kaiser/Newscom).[/caption]

Brandenburg, Germany: in three advanced economies—Germany, the United Kingdom, and France—emissions have fallen despite the increase in incomes (photo: Caro / Kaiser/Newscom).[/caption]

Economic growth has traditionally moved in tandem with pollution. But can countries break this link and manage to grow while lowering pollution?

Our research, based on joint work with Gail Cohen and Ricardo Marto, shows that yes, progress is being made. Our evidence is clear: advanced economies are starting to show signs of decoupling—increasing growth while reducing pollution—but emerging market economies not yet.

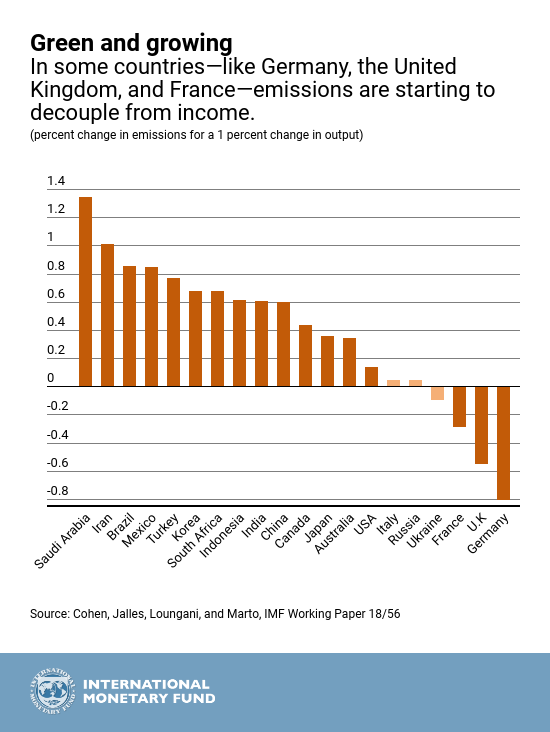

The chart summarizes our evidence on the link between the trend (long-run relationship) in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the trend in incomes. Our analysis covers the world’s top twenty largest GHG emitters from 1990 to the present. Over this time, incomes have grown—the trend is positive—despite dips due to occasional recessions and financial crises. But what has happened to trend emissions?

The bars in the chart show the percent increase in trend emissions for every 1 percent increase in trend incomes—economists refer to such estimates as elasticities. Look first at the three cases on the far right of the chart—Germany, the United Kingdom, and France. For this group the elasticity estimates are negative: emissions have fallen despite the increase in incomes. These countries have achieved decoupling of emissions and output. Our results show that this is due both to active policies by these countries aimed at decarbonizing their economies as well as the structural transformation of their economies towards a greater role for services.

In the next three cases, Ukraine, Russia, and Italy, we cannot be very confident of the relationship between emissions and incomes. Though the point estimates are close to zero, the confidence intervals do not rule out either much higher or much lower values; the bars in these murky cases are shown in a light shade.

The next four cases in the chart are all advanced economies, the United States, Australia, Japan, and Canada. These countries have elasticity estimates that are positive but small, between 0.1 and 0.4, which means that these countries have not achieved decoupling but emissions are growing at a much slower rate than incomes. In the United States, there has been strong progress since the mid-2000s, when trend emissions first slowed and then started to fall, mainly because of increased use of natural gas for electricity generation.

The remaining countries shown in the chart are emerging market economies. For this group, the elasticity estimates are all positive and exceed 0.6. Will these countries follow the path of the advanced economies? There are reasons to be optimistic. First, the elasticity estimates, while high, are lower than they were in the 1970s and 1980s. Second, in related research, we find that for countries such as China, the richer provinces are starting to show some signs of decoupling.

By providing evidence of progress with decoupling, we do not mean to downplay challenges. The control of emissions, while laudable, may not be enough to meet the goal of limiting the increase in global temperatures to below 2 degrees Celsius. Hence, as the IMF has long advocated, countries should consider carbon pricing—impose charges on the carbon content of fossil fuels or their emissions—to accelerate progress toward a green world.